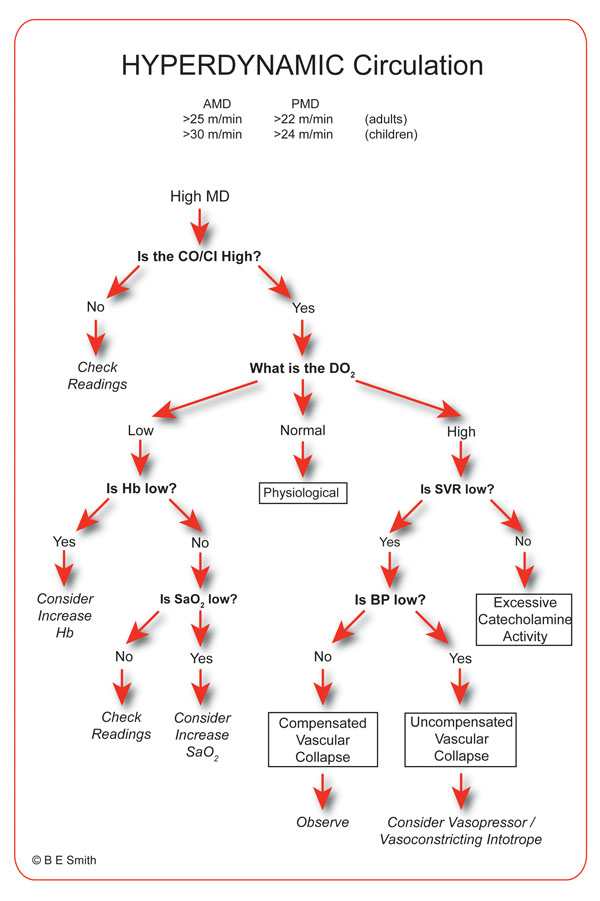

Section C - Hyperdynamic Circulation.

The most common cause of a hyperdynamic circulation is anaemia. If the haemoglobin concentration is low then the CO must increase to maintain oxygen delivery. If MD is >22 (28 in a child) then your first thought should be “what is the haemoglobin level?” There are also many physiological causes of a hyperdynamic circulation. Pregnancy, exercise, pain, fear and anxiety can all increase CO significantly, as well as pyrexia and hypercapnia. Could the high MD be due to one of these? If not, then let’s analyse the USCOM readings.

The most important question with hyperdynamic circulation is “what is the DO2? If the circulation is truly hyperdynamic then almost invariably it is because the body is asking for more oxygen to be delivered.

If DO2I is high, (greater than 500ml/m2/min) then we have a problem with oxygen uptake and utilisation, as in cytotoxic hypoxia, or there is a distributive problem, such as a shunt. A major fistula from the aorta to the vena cava (or multiple smaller fistulae) is an uncommon cause of this. If a hyperdynamic circulation is not due to anaemia, pyrexia, pregnancy, childhood or hypoxia / hypercapnia, then septicaemia must a critical consideration. An SVR of 600 can certainly be physiological, but 300 is almost certainly not! Look for pathological vasodilation as the cause of a high MD and high CO/CI. If DO2I is also high (>500ml/min/m2) then its pathological till proven otherwise!

One word of caution. If the SVR is low, BP is low and the CO high, then we are looking at high CO failure (HOCF) by definition. I would refer you to booklet 3 in this series, “The USCOM and Inotropy”, but beware of simple vasopressors! Very seldom is inotropy normal in this condition. A vasopressor may increase the SVR back to normal, but can the left ventricle cope with this increased afterload? If there is any significant myocardial depression then the answer is probably no. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) may be a wiser choice, or even balanced inotropes (see booklet 3, “The USCOM and Inotropy”).

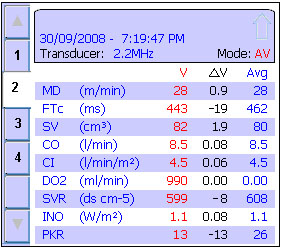

This 27 years old 82 Kg female has pneumonia. BP = 86/45 (MAP-59mmHg). What do you see?

Her MD is certainly raised at 28. We should therefore be thinking “what is the haemoglobin?” In this case it was 128g/litre, so anaemia is not the cause. According to the algorithm, the next question is “what is the DO2?” We can see that the answer is 990 ml/minute, but is this high, normal or low? To answer this we need to know what the DO2I is. Now, you were not given this but it is easy to work out. First we need the BSA. The CO is 8.5 L/min and the CI is 4.5 L/min/m2. BSA must therefore be 8.5/4.5 or 1.88 m2 as CI= CO/BSA. DO2I is thus 990/1.88 or 526 ml/m2/min, above the normal level of 500ml/m2/min.

According to the algorithm, the next question is “Is the haemoglobin low?”, but we know that it isn’t. The next question is “Is the SaO2 low?” Now again you haven’t been given this, but from DO2 = 1.34 x Hb x CO x SaO2/100, then if her Hb is 128 and her CO is 8.5 L/min, then if her SaO2 were 100% then the DO2 would work out as 1458 ml/min. Clearly her saturation is not 100%! In fact it must be 990/1458 or just 68%. So why is her circulation hyperdynamic? Easy – with a saturation that low, the CO has to be high to deliver enough oxygen to the tissues. But how did the heart know that? Well it didn’t, unless you say that the SVR told it! The SVR has fallen to 599, indicating a marked degree of vasodilation. Her PKR at 13 also indicates this. The heart didn’t know it, the tissues asked for it. With this degree of vasodilation it is not hard to see why she is hypotensive despite the high CO.

This example also illustrates how it is possible to calculate many of the parameters that you have not been given from those that you have. This shows the beautiful interlocking nature of all the variables in haemodynamics. You don’t have to measure everything to understand everything! From the pieces of the jigsaw that you do have it is easy to see what the missing pieces are.

So what conditions result in a hyperdynamic circulation? Here’s just a few!

Oxygen Delivery Problems:

Anaemia,

Haemoglobinopathies,

Hypoxia (global),

Shift in O2 dissociation curve,

2,3 DPG abnormalities,

Hypercarbia.

Cell nutrition problems:

Hypoglycaemia,

Hypoxia,

Hypophosphataemia,

Vit B deficiency,

Thyrotoxicosis,

Malnutrition.

Poisoning:

Septicaemia

Carbon monoxide,

Cyanide,

Evenomation,

MDMA / Amphetamines

Antihypertensives

Histamine releasers

(e.g. anaphylaxis)

These lists don’t include iatrogenic causes such as excessive vasodilator therapy with sodium nitroprusside, ACE inhibitors, frusemide or hydralazine. Did I mention heat stroke? Get the idea? Vasodilation is at the heart of a hyperdynamic circulation. The question we have to answer is simply – did the tissues ask for this much blood and oxygen or was it inappropriate (i.e. pathological) vasodilation?

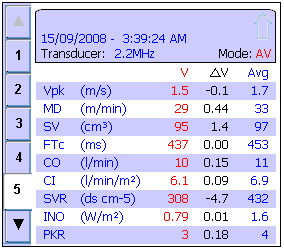

Another example of hyperdynamic circulation; take a look at this set of USCOM data.

This is a 32 years old, 53kg female. She was admitted to ED as “sudden collapse at home after feeling unwell for about 12 hours with a ‘flu-like illness”. Her BP is 56/31 (MAP-39mmHg). Her GCS is 8. She was previously well and takes no medication apart from the oral contraceptive pill. Her haemoglobin was 134g/litre and her SpO2 was 94%. Acute pulmonary embolus was being considered. Do you agree with the provisional diagnosis?

A bit more data might help, so can we calculate it from the data we have?

From CO/CI we can work out her BSA must be 1.64m2. Her Stroke Volume Index (SVI) must be 95/1.64 = 58ml/m2, or 1.8ml/kg – very high. We can work out her DO2 as 1.34 x 134 x 10 x 94/100 = 1688 ml/min. From this and her BSA we know her DO2I = 1688/1.64 = 1029 ml/m2/min which is well above normal. You might already have worked out that her heart rate is 105.

So what does all this mean? She is clearly hyperdynamic. It is not due to anaemia. Her DO2 is very high, her SVR is very low and her BP is very low. According to the algorithm, this puts us fairly and squarely in the category of decompensated vascular collapse. But a PKR of just 3 told us this straight off. Something is clearly depressing her inotropy, to the extent of clinical left ventricular failure (see booklet 3, “The USCOM and Inotropy”). This isn’t pulmonary embolus; this is full-blown septic shock!

How will you treat her? Does the FTc or SV/SVI indicate that she needs fluid? If her Smith-Madigan Inotropy Index (“INO”) is just 0.79 will she respond to fluid? Would extra oxygen help? What would happen if we treated her with positive pressure ventilation? If you have come this far with the four USCOM booklets then you already know the answers to these questions. Congratulations, you’re now ready to fly solo!

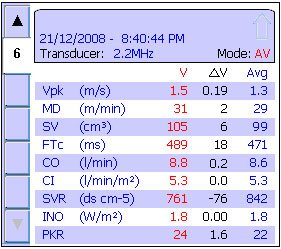

On a cheerful note, here’s a set of USCOM data from a 23 year old 78Kg female with a blood pressure of 100/70 (MAP-83mmHg). She’s fully conscious, apyrexial and quite happy to be in hospital. What is your diagnosis?

You might be interested to know that just an hour or so after this reading was taken she became a mother! Not all hyperdynamic states are pathological, unless of course you consider children to be little pathogens! Let’s not go there... |